Damages for the damnified? What DOES Law of Property Act s 104(2) mean? 10 January 2024

Section 104(2) is frequently used to ease the conveyancing process when a mortgagee sells the security: it enables the mortgagee to pass good title to a purchaser even if the exercise of its power of sale is unauthorised, improper or irregular. The corollary of that power, the obligation to pay damages if a wrongful sale occurs, has, until recently, received little attention. This article high-lights two recent cases, explains what we can learn from them, and sets out some thoughts on the remaining unanswered questions arising out of this provision.

The Lender’s Power of Sale

The primary remedy which most secured lenders will want to exercise if the customer defaults is to sell the security and recoup its loan, or as much as possible of it, from the proceeds. The lender’s statutory power of sale derives from Law of Property Act 1925 s101, but there will almost always be restrictions preventing the exercise of that power of sale, before certain conditions are met. If a lender sells the Property before it is entitled to do so, the lender’s act is wrongful.

Section 104(2) of the Law of Property Act 1925

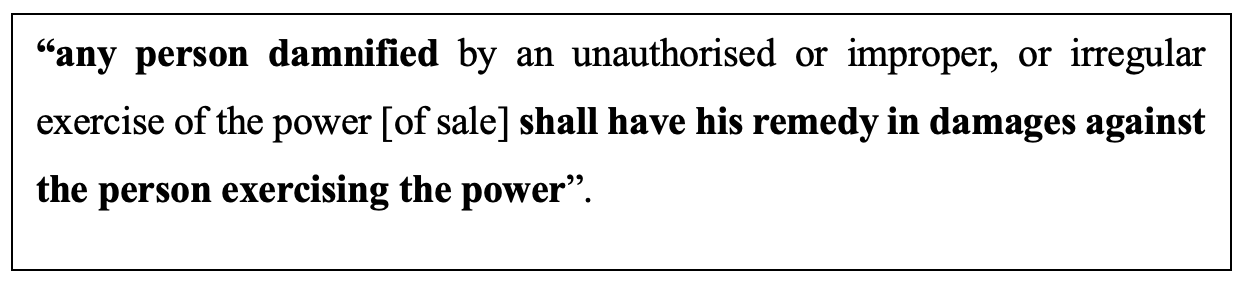

Section 104(2) provides that

The provision gives rise to two principle questions:

No guidance is given in the statute (or in the previous statutes from which it was derived) about the answers to these questions. It is therefore necessary to approach the matter from first principles, with such assistance as is available from the authorities. Any question of statutory interpretation requires a consideration of the natural meaning of the words used, the legislative scheme as a whole and the legal context in which the statute was enacted.

A new cause of action?

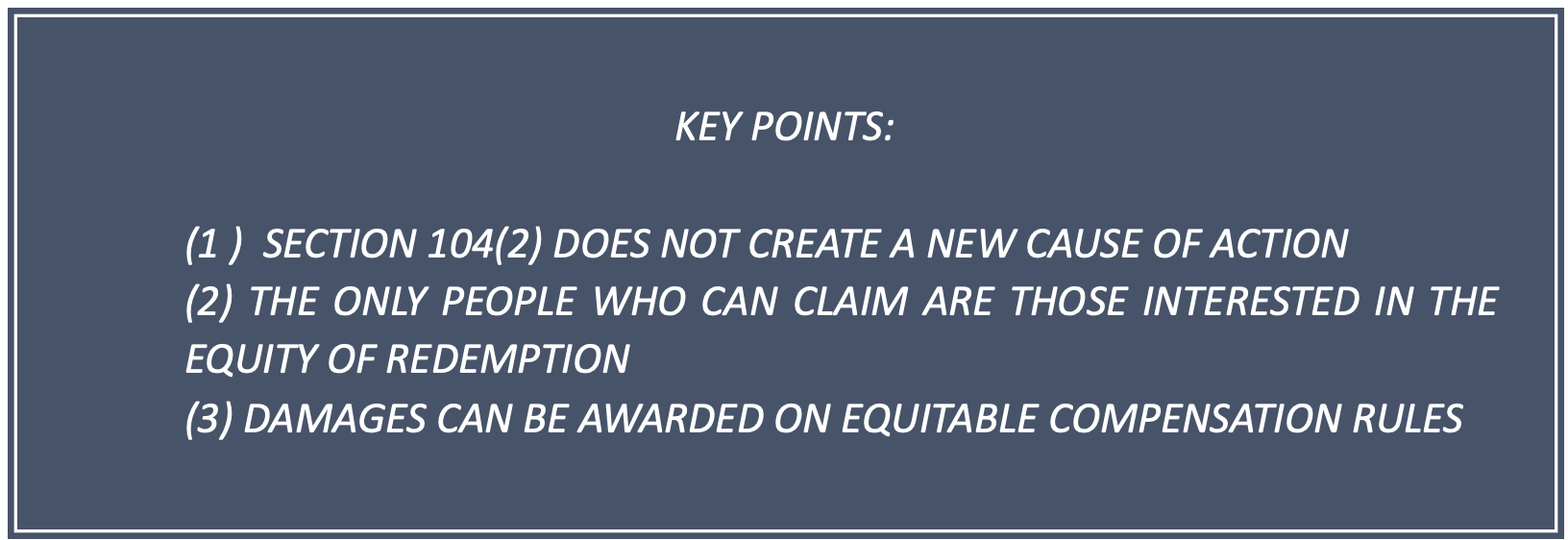

A sensible starting point is to determine the legal context. Although this has not been the subject of any authority in the English courts, the Australian courts determined as long ago as 1935, in McGinnis v Union Bank of Australia Ltd [1935] VLR 161, that:

- prior to any statutory intervention, the Courts of Equity would have directed the lender to account on the basis of wilful default if it sold the security before any right to do so had arisen; and

- that a very similar provision in the Transfer of Land Act 1916 s 9(b) did not create a new cause of action.

We consider it likely that an English Court would adopt the same approach. On this basis, the wording of the provision merely clarifies that the mortgagor retains a remedy in the event of a wrongful sale, notwithstanding that the purchaser will get good title. This sheds a good deal of light on the answer to the two questions posed above.

A person ‘damnified’

Although the language is somewhat old-fashioned, we consider that the ordinary meaning of this word is reasonably clear: it means a person who has been caused injury. It is clear that the class extends to persons other than the mortgagor. The real question is whether there is anything about the context which excludes some people who have been caused injury by the wrongful sale from claiming damages.

In Kallakis v AIB [2023] EWHC 2148 (Comm), the Commercial Court had to determine whether a lender owed a duty to a person with an indirect beneficial interest in the entity which owned the entity to whom misrepresentations were alleged to have been made. It was argued that the wide wording of section 104(2) suggested that a lender would owe duties to a wide class of people, including the claimant. The Court rejected that submission: it said (at [182]-[183]) that a person in the claimant’s position could not claim damages under section 104(2), suggesting that only a person with a proprietary interest in the property could bring such a claim.

In fact, we do not consider that is quite the right test. We do not consider that someone with, say, the benefit of a restrictive covenant over the land which was not protected by registration at Land Registry, so that the purchaser took free of it, would be able to claim against the lender if, by happenstance, the lender had wrongly exercised the power of sale. The lender’s duty to account is owed to all those interested in the equity of redemption, but not to others: Silven Properties Ltd v Royal Bank of Scotland plc [2004] 1 WLR 997 at [19]. We therefore consider that the only persons who can claim under s 104(2) if they are “damnified” as a result of a wrongful exercise of the power of sale are persons interested in the equity of redemption.

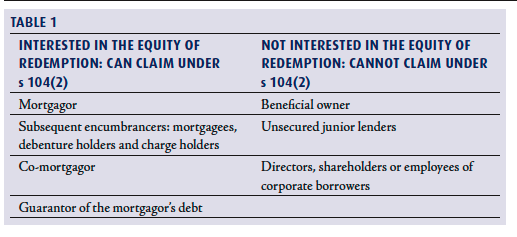

In CPF One Ltd v OSK (UK) II Ltd [2023] EWHC 2102 (Ch), the court summarised (at [37]-[38]) who was interested in the equity of redemption. The point was also considered in Kallakis at [192]-[193]. On the basis of these cases, and the leading authority of Downsview Ltd v First City Corpn Ltd [1993] A.C. 295, the position can be summarised in Table 1 below

Damages

How are damages quantified? In McGinnis, the court said:

“The relief claimed as damages is in substance identical with that which a Court of

Equity would … grant by directing an account by the Defendant on the basis of wilful default.”

This means the lender would have to account to the mortgagor and all others interested in the equity of redemption not just for what he actually received, but for what he should have received, had the wrongful sale not occurred: Silven (supra). In order to consider what this might mean in practice, it is necessary to differentiate two types of cases:

Sale possible

We consider that it will be extremely difficult for claimants in the first type of case to establish any loss. The comparison there will almost always operate on the basis that a sale would have occurred anyway, and the

question is whether the purchaser would have paid any different price if the sale had not been wrongful. The purchaser will get a good title as a result of the “statutory magic”,

so the fact that the sale is wrongful provides no reason for the purchaser to pay less than full value for the property. (Of course, if the lender failed to take reasonable care to achieve a proper price, the borrower could claim damages for breach of the equitable duty whether the sale was wrongful or not without having to rely on s 104(2): Cuckmere Brick Co v Mutual Finance [1971] Ch. 949).

Sale not possible

A claimant may be able to show that had the sale taken place later, the property might have increased in value – or that he would have received more if the sale was later for some other reason, such as he would in the meantime have been able to clear off a wrongly registered prior charge. Here the assessment of damages would be reasonably straightforward: one simply compares the amount the claimant received from the wrongful sale and the amount he should have received from a later, rightful sale. We consider that this is not simply a question of comparing the net proceeds of sale: it is also necessary to consider whether, say, the mortgagor has lost profit that it would otherwise have made from the property during the period prior to the rightful sale, or, conversely, any extra costs which the mortgagor has incurred during this period.

If a claimant borrower could show that he would have been able to prevent a sale occurring at all (for example because he would have remedied the default, or redeemed the mortgage before the power of sale arose) much more interesting questions arise. Is the borrower to be confined to the difference between the sale price and the value of the property (if any)? If so, the section adds little to the ability to claim damages in the event of a sale at an undervalue (which exists even if the power of sale is validly exercised), and risks leaving the borrower undercompensated. That does not feel right.

And it is not, in our view, right in principle either. The claim is based on breach of an equitable duty. Equitable compensation rules, not common law damages rules, ought, therefore, to apply. This means that compensation should be assessed at the date of the trial, with the benefit of hindsight, so that whether the losses were foreseeable should be irrelevant: AIB Group (UK) plc v Mark Redler & Co Solicitors [2015] AC 1503 at [135]. The borrower should be able to recover any losses which arise, so long as there is some reasonable causal connection between the breach of duty and the losses claimed, by analogy with the rule that is applied when a fiduciary is obliged to account for profits made by reason of a breach of duty: CMS Dolphin Ltd v Simonet [2001] EWHC 415 (Ch) at [97]. In our view, there is scope for a significant claim in this scenario.

This article first appeared in the December issue of Butterworths Journal of International Banking and Financial Law.

Disclaimer: This article is provided for educational purposes only. It is not intended to, and does not, give or contain legal advice, and it should not be relied on as a basis for taking any course of action or for the purposes of giving legal advice.

Download: Damages for the damnified? What DOES Law of Property Act s 104(2) mean?

Back to articles